March 25: There is little doubt that Canada currently faces a crisis which has the potential to significantly change the character of our country. In the face of unprecedented interference from US President Trump, the way in which our governments react will will dictate the nature of our country for decades to come.

As Paul Romer, a Stanford economist and co-recipient of the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2018 said: “A crisis is a terrible thing to waste.” We now have an opportunity – disguised as a crisis – to fundamentally reimagine our country. We need to break away from many of the current orthodoxies and long-standing impediments that have stood in our way. We can make a better Canada, if we choose to do so.

What we can’t do, is carry on “business as usual.” As one of our politicians has described it: “We must break down interprovincial trade barriers, open internal markets, lower taxes, reduce subsidies, thin regulation, get our resources out of the ground, build export-oriented infrastructure, and make it a national mission to diversify our external markets.” Stephen Harper was expounding on the “neo-liberal” strategy that he implemented almost a decade ago and which has left us in our current state. The fact that the Trudeau years did so little to alter this approach to economic strategy shows the stasis of political thinking in our country, and the deep-seated lack of desire to alter course.

What we can’t do, is carry on “business as usual.” As one of our politicians has described it: “We must break down interprovincial trade barriers, open internal markets, lower taxes, reduce subsidies, thin regulation, get our resources out of the ground, build export-oriented infrastructure, and make it a national mission to diversify our external markets.” Stephen Harper was expounding on the “neo-liberal” strategy that he implemented almost a decade ago and which has left us in our current state. The fact that the Trudeau years did so little to alter this approach to economic strategy shows the stasis of political thinking in our country, and the deep-seated lack of desire to alter course.

It’s therefore deeply disappointing to me that both Carney and Poilievre have been quick out of the gate promising tax cuts of different magnitudes and for different constituencies. Reducing taxes generates less revenue for the government to allocate to its programs and priorities. With less revenue to go around, many of our fundamental institutions, like hospitals, the military and universities, have become and will continue to be inadequately funded because the government has cut funding to “balance the books”. They are therefore deteriorating at an alarming rate. Current tax policy has created a society where the most economically well-off are getting richer, and the poor are falling further behind. The so-called “middle class” has essentially disappeared. Allowing industry greater control over the regulatory system has meant greater corporate profit, continued threats to the environment and the risk of continued loss of decent well-paid jobs to overseas competition. It’s early days in our Federal election and I am hopeful that there will be more thoughtful policies from both parties. I also hope that our political class will return to the idea of being “statesmen” and actually work together to make the country a better place, rather than simply looking to score points toward the next public opinion poll.

There are opportunities now to consider how we trade with other countries around the globe. We can no longer rely on the American market as the country has become unreliable at best, and an enemy at worst. We need to consider global security and assume a more proactive role in securing our own borders – particularly in the arctic – with a stronger and more modern military presence. We should take the step that tripped Justin Trudeau and eliminate the “first past the post” electoral process and adopt a proportional election system for future elections. And while we are at it, let’s re-write our tax structure so that everyone pays a fair share, and there are fewer special interest groups hived off into lower or preferential tax brackets.

Now is not the time for half-hearted measures. We have seemingly come together in the face of an existential threat. Whatever we do next, let’s be bold. Our response – expressed most immediately through our electoral process – demands nothing less.

Globe editorial: What this campaign is missing: a real vision for a new Canada – The Globe and Mail

Opinion: Canada’s existential election has very quickly become unserious – The Globe and Mail

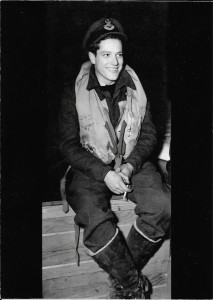

He also spoke of waiting in line to take off on a night mission. The first aircraft in line would be given a green light, signifying that it was clear to take off. When they had cleared the field, the next in line would be given the green and off you would go. On this particular night, one of the aircraft ahead of Dad’s plane had attempted takeoff and collided with trees near the end of the runway. There was a massive explosion (being fully fueled and loaded with bombs), and then a brief pause before the next plane was given the green light.

He also spoke of waiting in line to take off on a night mission. The first aircraft in line would be given a green light, signifying that it was clear to take off. When they had cleared the field, the next in line would be given the green and off you would go. On this particular night, one of the aircraft ahead of Dad’s plane had attempted takeoff and collided with trees near the end of the runway. There was a massive explosion (being fully fueled and loaded with bombs), and then a brief pause before the next plane was given the green light.